Luck? No such thing…

This is a guest post by Dr Sara Shinton, Head of Researcher Development at the University of Edinburgh.

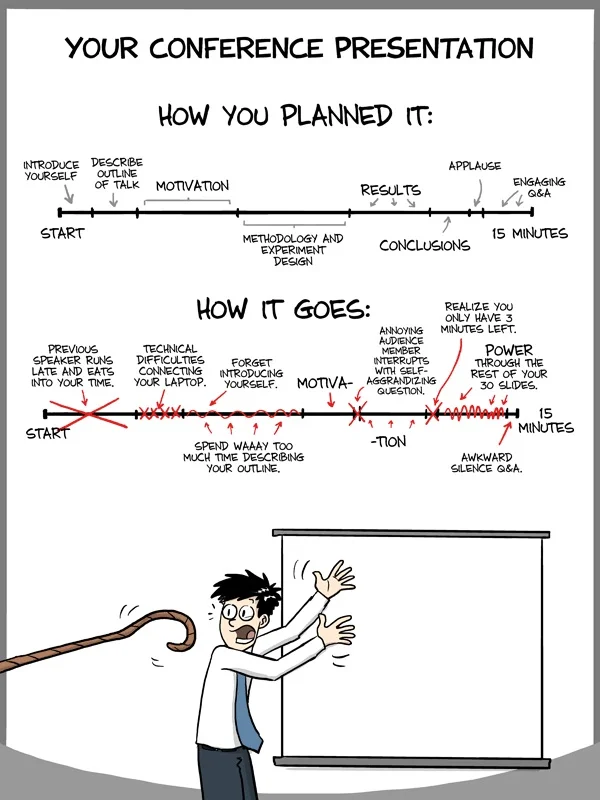

Part of my role as Head of Researcher Development involves running leadership programmes, often with guest speakers. This means I listen to a lot of senior and successful people talking about their careers and the challenges they’ve faced. People have always spoken freely about their career paths, but it’s been interesting to note that when pushed about how an opportunity came about, many will refer to their “luck”.

Although I understand the sentiment – a combination of humility and recognition of how important other people are in our successes – the trouble is that this can be frustrating for early career academics to hear. This is particularly the case if the guest started their academic career fifteen or twenty years ago, as the audience can feel that luck was in abundance then, but now? Not so much.

Last year I was invited to talk to the University of Glasgow Women in Research Network (WIRN) about networking. Instead, I decided to make “luck” my theme. I wrote a blog post about this event earlier, but was invited to address this topic to PGR students at the University of Glasgow. I’m delighted to do this because it’s important to recognize how much luck we can bring towards ourselves.

First, think about how luck might manifest itself in your life. What would you look like if you were luckier? The WIRN group talked about more success with grant income, a permanent position and intellectual freedom. I told them that I felt very lucky to have been invited to talk to them. However, it wasn’t down to luck – there were a series of steps that brought this opportunity to my door and most involved elements which were in my control:

Someone in my network suggested my name

This person knew that I was interested in women’s development

My online presence gave a reasonable sense of who and I am and what I do

I said yes (even though I doubted I was the right person once I realized how illustrious previous speakers had been)

What would the steps look like if you were successful in getting a grant awarded? Here’s a suggested breakdown:

I wrote something that both reviewers and panel members thought was worth funding

I had the skills and experience to convince them I could do this work and manage the funding effectively

I applied for the right scheme with the right funder, so my ideas fitted their objectives

I applied, despite previous failures

This isn’t to deny that there is a lot of luck involved in grant funding. There are now so many “fundable, but not funded” projects that those below the cut-off point are often simply unlucky. Despite this, there’s a lot you can do to tip the odds towards your favour:

Get as many different people to read your drafts so you can present your ideas to both the close-expert reviewer and the widely-knowledgeable panellist.

Look at the gaps in your track record and ask around your network for opportunities such as work-package management (if you aspire to coordinating large grants), industrial consultancy (if you have an eye on the Industrial Strategies Challenge Fund) or for funding for short visits (if you need to add to your portfolio of skills or provide evidence of research relationships). Look at the profiles of successful applicants if you aren’t sure what is missing from your CV.

Get to know the UofG Research Support Office and ensure they know about your research interests and longer term vision – they may know of schemes which are narrow in focus, but right for you.

Keep on applying despite the demoralising impact of failure. Find a way to manage the disappointment and to learn from each application!

Much of the luck experienced by successful people is down to their reputation and networks because these factors bring opportunities. So, what can you do as an early career researcher to be luckier? I presented ten ideas in the original blog on this subject, but I’m going to focus on three, partly for brevity but mostly because they are the most important and focus on the key point – luck is often about being visible to other people who can share opportunities.

Know what you want

Tell people what you want

Ask them how you might get it

That’s it. Simple, eh?

Know what you want

Take your headline career goal and break it down so there’s enough detail in it to identify specific actions to take or seeks advice on. Want a permanent position? Look at the promotion criteria for the grades above you which tend to reflect a permanent status. Look at job descriptions and adverts. Ask your Head of School what convinces her or him to offer someone a permanent post. Now you should have some clear goals.

Tell people what you want

Don’t take for granted that everyone knows your career plan. One of the most interesting experiences in my career was running one-on-one careers advice appointments with research staff. I met a person who had a great CV and he couldn’t understand why he wasn’t progressing. He told me “In the last four years, there have been three lectureships available in my department and no-one has suggested I go for one.” (You probably know where this is going.) I suggested that he make an appointment to talk to his Head of School and to explain that he wanted a lectureship and to ask for advice. He emailed me four months later to say he now had a lectureship in his school. His Head of School had assumed he enjoyed being able to focus on his research, even on contracts because there had been three opportunities to apply for a lectureship over the last four years and he hadn’t applied for any of them. Are you making assumptions about what others think? Are you missing out as a result?

Ask them how you might get it

The final step makes use of the detail you added to your goal in step one. A mentor will talk to you about the big questions “How do I get a job? How do I get money? How do I publish a career-defining paper?” but you want to spread your net wider. Look at the breakdown of your goal and ask people around you how you might “demonstrate an international network” or “look like you can be trusted to manage the finances of a grant”. As your confidence grows, you should be more specific and ask if they might connect you with a key collaborator or let you take responsibility for managing aspects of a larger project.

Don’t leave your career down to luck – take control and put yourself on people’s radar. Great things will follow.

More information

GRADschool is a three day course designed to help 2nd and 3rd year PhD researchers to practice skills such as communication, networking, leadership, influencing, team working and time management. This is a perfect course if you want to develop goals for the next steps in your career!

For general questions regarding researcher development, feel free to contact the UofG’s Researcher Development team here.